Wellington the Hero

Wellington Defeats Napoleon and a Grateful Nation Hails Him as a Hero

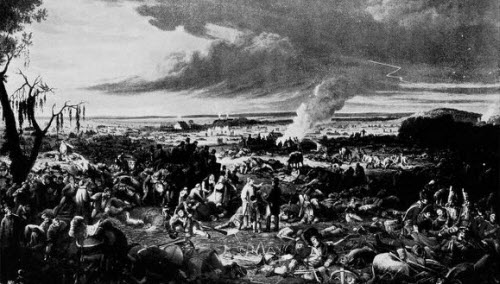

After the Battle of Waterloo

In 1814, during the brief peace that followed Napoleon's first abdication and his exile to Elba, Wellington was appointed ambassador-extraordinary to France and in this capacity journeyed to the Congress of Vienna, where the victorious allied powers were deciding on how Europe would be carved up and what would be done with conquered France.

However the Congress was abruptly broken up when it was learned that Napoleon had escaped and was once again in control of France. Wellington was immediately appointed commander of the British forces in Europe, then concentrated in Belgium, together with the allied armies of Prussia under Blucher.

Moving boldly, Napoleon attacked seeking to destroy the allied forces before they could unite against him. The battles of Ligny (q.v.) and Quatre Bras (q.v.) were followed on June 18, 1815, by the great battle of Waterloo (q.v.).

Till now, Wellington had only fought against Napoleon's generals. Here, at Waterloo, the French Emperor and Wellington met in battle for the first and last time. And it is here, at the Battle of Waterloo, that Napoleon was decisively crushed. The allied armies under Wellington and Blucher now marched on Paris. The French army was allowed to evacuate the capital under a truce, and the French king Louis the XVIII was restored to the throne. Napoleon abdicated and was taken prisoner by the British and then sent to the island of St Helena, from whence he would never escape, except in death. Napoleon's Marshal Ney, who had fought alongside the Emperor at Waterloo and rallied the defeated army, was tried and condemned to death as a traitor by the French King. Ney relied upon the terms of the capitulation of Paris, and appealed in vain to Wellington, who in a rather shameful episode denied that the French king was bound by the convention, a reading which it is impossible to justify. As a result the brave Marshal Ney was executed by firing squad.

Wellington now took command of the army of the occupation and from 1815 to 1818 resided in Paris. During this time, there were a couple of attempts on Wellington's life by French patriots. In one instance his cellar was filled with gunpowder and the conspirators planned to blow up his house, but the plot failed. On another occasion a French officer named Cantillon shot at Wellington when he was riding in his carriage through occupied France. The French officer was acquitted by a French jury and it is a measure of how much Napoleon blamed Wellington personally for his defeat at Waterloo, that the former Emperor left Cantillon a substantial legacy in his will, expressly thanking him for his attempted assassination of Wellington.

In 1818, the allied forces finally left France and Wellington returned home. More honours were bestowed on him. Napoleon was created prince of Waterloo by the King of the Netherlands, field marshal of the Prussian and Austrian armies and in Britain numerous statues were erected in his honour. Parliament also voted an additional reward to Wellington of £200,000. A national hero, Wellington's political fortunes continued to rise. He held the prestigious post as lord high constable of England during the coronation of George IV., in 1821,. In October he accompanied George IV. on a tour of the field of battle at Waterloo. In 1826 he was sent on a special embassy to St. Petersburg, Russia, where he persuaded the Russian Emperor to join with England and other powers to mediate the dispute between the Ottoman Empire and Greece.

In recognition of his services, Wellington was appointed to the honorific post of Constable of the Tower of London. In 1827 he succeeded the duke of York as commander-in-chief of the army, and was made col. of the Grenadier guards. In Aug., 1827, he again accepted the command of the army, but he resigned this position when called upon by King George IV. (Jan. 8, 1828), to form an administration and Wellington began his first term as prime minister.

Wellington's Funeral

Although Wellington was a staunchly conservative Tory in his political leanings, his administration brought in what were considered radically liberal reforms including legislation to remove Catholic civil and political disabilities, which had barred Catholics from holding office. This reform was brought in by necessity to avoid a civil war in Ireland but was nevertheless opposed by Wellington's fellow Protestants. So bitter was Protestant opposition to granting Catholics any political rights, that Wellington became involved in a duel with the Earl of Wincheslea over this issue; both men survived. However he also resisted calls for parliamentary reform which would have made the parliament more representative of the popular will; and he was driven from office due to his growing unpopularity.

Despite being a national hero, Wellington's unpopularity over his opposition to parliamentary reform resulted in him being assaulted and pelted with rocks by angry mobs who broke the windows of his house. Wellington was forced to resign as prime minister. He was elected chancellor of Oxford University and later recalled by the King and served temporarily in a caretaker government in 1834.

At the coronation of Queen Victoria, France was represented by his former enemy Marshall Soult whom he had fought many times. Wellington gave his former adversary a warm welcome.

In 1841 Wellington accepted a seat in the cabinet of sir R. Peel, without portfolio. In 1842 the queen visited him at Walmer castle, and in the same year he was re-appointed to the command of the forces.

In 1845 Wellington addressed the House of Lords and eloquently advised them to vote in favour of the repeal of the unpopular Corn Laws despite his personal opposition to the measure, because he felt that the House of Lords should not oppose the will of Parliament. As a result, the measure passed with a substantial margin and Wellington regained some of his personal popularity. When the Peel government resigned in 1846, Wellington also resigned from office and left public political life.

However Wellington continued to be involved in military affairs and championed military reforms, including the establishment of a strong militia to provide a pool of trained soldiers in the event of war.

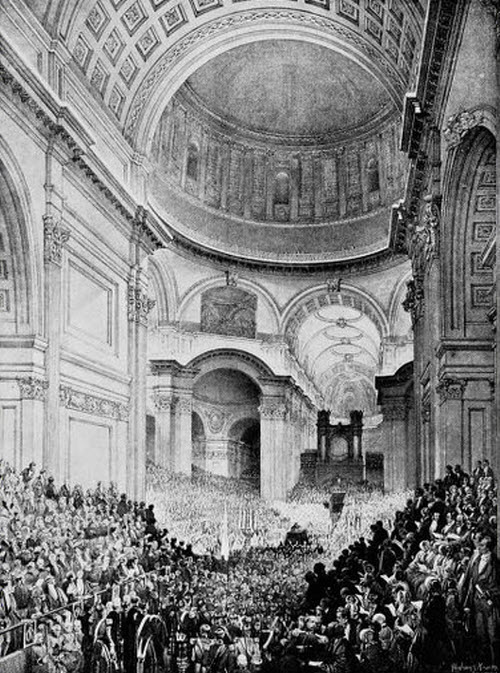

On Sept. 14, 1852, Wellington suffered an apparent stroke and lost the ability to speak; he died later that same day. He was honoured with a large public funeral and was buried next to the body of Lord Nelson in St. Paul's Cathedral.

.jpg)